The Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) was a youth-led civil rights organization whose impact on the civil rights movement was monumental. Before SNCC, most civil rights leaders were adults, with only a few exceptions like the Southern Negro Youth Congress (SNYC) in the 1930s and ’40s. While the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) had some young leaders in the 1960s, SNCC would eventually have more people working full-time in southern communities than any other civil rights organization. Student activists increasingly rose to prominence as the sit-in movement, which college students in Baltimore, Maryland had begun organizing as early as 1953, gained momentum. On February 16, 1960, Martin Luther King Jr. spoke about the sit-in movement at the White Rock Baptist Church in Durham, North Carolina, saying, “What is new in your fight is the fact that it was initiated, fed, and sustained by students.”

Renowned organizer Ella Baker was instrumental in SNCC’s creation and served as a mentor for both the organization and its members. Baker convinced the Southern Christian Leadership Conference to bring together young activists just a few months after the famous Greensboro, NC sit-ins in 1960. Baker sent Robert “Bob” Moses on a journey through the Deep South to recruit students to participate in an SCLC conference planned for October 1960. At the gathering, the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee was established.

In its early days, SNCC’s focus remained on direct action, particularly the sit-ins that aimed to desegregate lunch counters and restaurants. Discussions on how to spread the sit-in movement dominated. Prominent politicians, such as President John Kennedy and his brother, Attorney General Robert Kennedy, were hostile to direct action and began pressing SNCC to refocus their efforts to voter registration.

This shift, from direct action to voter registration, was not simply a question of logistics but rather an ideological question of whether the problem at hand was a moral or political one. Some SNCC members viewed the problem of white supremacy as a moral issue and believed that direct actions created a more crisis of conscience that could move white people away from discriminatory behavior. Those who wanted to pursue voter registration believed the problem of white supremacy was political – about power – so political power was needed to fight it. The Kennedys believed that focusing on voter registration would anger Southerners less than the focus on direct action.

Ella Baker stepped in to explain that the people down South would not make this sort of distinction. There would be anger and the potential for violence whether organizers were holding sit-ins or voter registration drives. With the help of Baker, SNCC’s leaders came to see the value in both the moral and political approaches. She then helped the young SNCC organizers establish both a direct action and voter registration wing. Baker was also key in helping establish other core tenants of the organization, such as a grass-roots focus that helped a group of only a dozen people make such a huge difference on the Civil Rights Movement.

SNCC slowly evolved into an organization of organizers, embedding themselves in rural communities where they helped local individuals and community organizations create their own action plans. Many of these efforts in rural areas gave special emphasis to voter registration. SNCC’s first voter registration effort began in McComb, Mississippi, which was the most Klan-ridden region in the state, in the late summer of 1961. Despite encountering heightened violence, some 80,000 Black people where registered.

In 1964, SNCC helped organize Freedom Summer with a dual focus on education and voter registration. The plan was to assemble volunteers, predominantly white students from the north and the west, to be trained and deployed to areas throughout the Deep South. All volunteers would work with and under the direction of SNCC and local organizers. Some volunteers served as teachers at Freedom Schools where they taught community members of all ages about subjects ranging from literacy to civics, including specific directions on how to do things like registering to vote or opening a bank account. These volunteers were aware that they were risking their lives to see SNCC’s plan to fruition. Before volunteer training in Ohio was even completed, three activists in Mississippi went missing. While searching for these activists, the bodies of five additional Black men were recovered. As the summer went on, scores of SNCC organizers and volunteers were threatened, followed, beaten, and arrested.

In April 1964, SNCC workers helped with the organization of the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party (MFDP) to challenge the legitimacy of the all-white state Democratic party. Some white supremacists argued that Black voters could register, they just did not care about voting and therefore were not registering. Voter registration efforts countered this narrative by showing that it was not a lack of desire to vote but intentional misinformation, Jim Crow laws, and outright violence that prevented Black citizens from registering and voting. While local white officials could ensure that the state Democratic party remained virtually all-white, organizers could register citizens of all races to the new MFDP. In August, an MFDP delegation went to the Democratic Party national convention in Atlantic City, New Jersey, to challenge the legitimacy and seating of the all-white Mississippi delegation there.

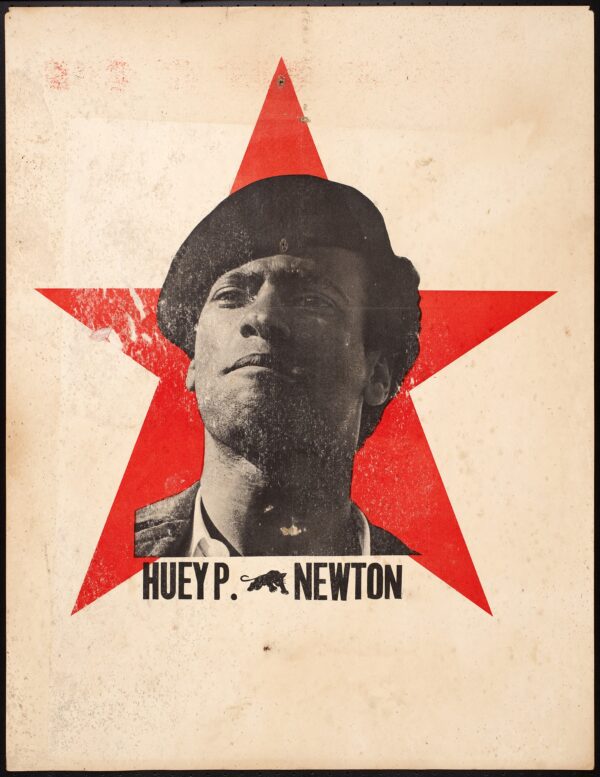

The power of the testimony of SNCC Field Secretary and native Mississippian Fannie Lou Hamer on live television was so immediately evident that President Lyndon B. Johnson called for an immediate press conference to try to get her off the air. Ultimately President Johnson’s party politics, because of some back room dealing, won out over the morally and legally just challenge of the MFDP and their delegates were refused seats at the convention. These events directly influenced future SNCC chairman Kwame Ture to use different tactics when he helped to organize the original “Black Panther” party in Lowndes County, Alabama.

![A black and white pin-back button with text. In two arcs around the top and bottom edges of the button face are black blocks with white text. In the middle, centered, is black text. The text reads: [STUDENT NONVIOLENT / WE / SHALL / OVERCOME / COORDINATING / COMMITTEE].](https://learn.civilandhumanrights.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/LP13_Figure-9-600x599.jpg)