After the rejection of the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party (MFDP) in Atlantic City, Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) campaigned for Lyndon Johnson and challenged Mississippi’s congressional delegation. Some in SNCC discussed the need for an independent Black political party in Mississippi but were unwilling to fight the MFDP, which was still led by local community leaders. “You can’t say that people have a right to make the decisions affecting their lives and then turn around and fight them because they made a decision you disagree with. The MFDP belongs to the Mississippians, not SNCC,” said one SNCC organizer.

In March 1965, a group from the SNCC used the Selma-to-Montgomery March to connect with interested Black residents and start organizing in Lowndes County, Alabama. The SNCC had been organizing in Selma since February 1963 but had not yet extended its efforts to Lowndes County. Even though Lowndes County had an 80 percent Black population, there were no Black people registered to vote except for a few who had applied two weeks prior to SNCC’s arrival and were waiting for confirmation.

Led by Stokely Carmichael, this SNCC group was determined to establish an independent Black political party. They found a willing partner in John Hulett, who had already formed the Lowndes County Christian Movement for Human Rights with a small group of other Black residents. Together with the SNCC, they formed the Lowndes County Freedom Organization (LCFO), with Mr. Hulett serving as its chairperson. The party adopted the symbol of a pouncing black panther. Within a year after the passage of the 1965 Voting Rights Act, most voters in Lowndes County were Black. In 1970, John Hulett, part of the group trying to register to vote before SNCC’s arrival, was elected as the county sheriff.

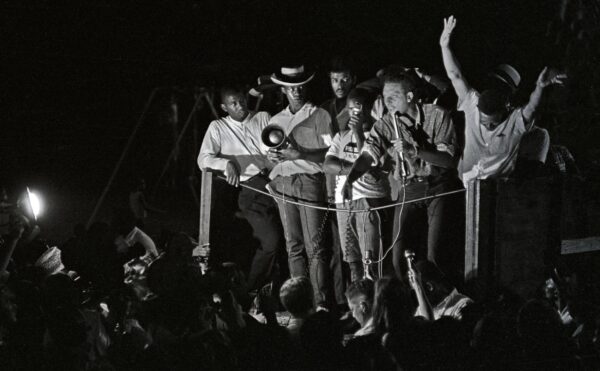

After the Lowndes County Freedom Organization transformed into the Black Panther Party, similar parties started forming throughout the country. By 1966, the organization’s leadership had moved to a more militant position, with Black Power advocate, Stokely Carmichael replacing John Lewis as chair of SNCC. In Oakland, California, the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense was established in 1966. Led by Bobby Seale and Huey Newton, they organized young and poor Black community members into the Black Panther Party. Like Malcolm X, the Black Panthers believed that nonviolent protests were not enough to free Black Americans or give them control over their own lives. Their ideology was one of Black nationalism, self-defense, and socialism.

The party’s founding document was the Ten Point Plan, which was widely distributed as a means of propaganda, education, and recruitment. The party also initiated various pioneering community programs, mostly led by women, in the Oakland area. The most famous and successful of these programs was the Free Breakfast for Children Program, which began in a San Francisco church and fed thousands of children throughout the party’s history. Today, public schools’ free breakfast programs are a legacy of the Black Panther Party.

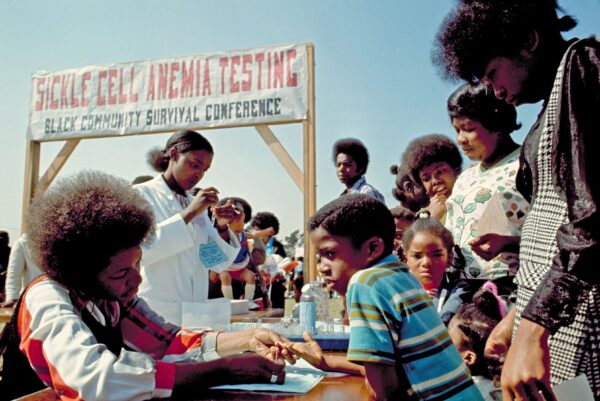

Other free services offered by the Black Panthers included clothing, classes on politics and economics, medical clinics, lessons on self-defense and first aid, transportation for family members of inmates to upstate prisons, an emergency response ambulance program, drug and alcohol abuse rehabilitation, and testing for sickle-cell anemia. The Panthers tested over 500,000 community members for this disease before it was officially recognized as mainly affecting the Black community. The Party also worked to end drug use in the Black community by disrupting drug dealers, distributing anti-drug propaganda, and setting up community drug rehabilitation programs.

In 1967, the Black Panther Party organized a march on the California state capitol to protest the state’s attempt to prohibit carrying loaded weapons in public. March participants carried rifles., The police used this as an excuse to subject the group to prosecutions, shootouts, assassinations, investigations, and surveillance.

While some members of the organization focused on community programs and services, others became involved in confrontations with the police. The separation between political action, criminal activity, community services, access to power, and grassroots identity became confusing and contradictory. Eventually, the Black Panther Party fell apart due to rising legal costs and disputes.