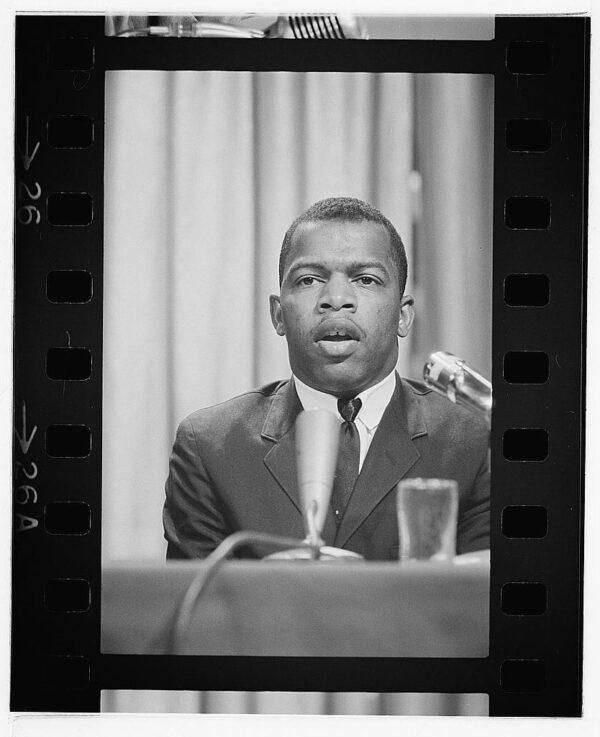

The Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) was made up of young activists and organizers who played a big role in the civil rights movement. From its outset, SNCC included both young Black and white students. This was the first time that young people were leaders in the movement. They focused on organizing from the bottom-up and helped bring new voices to the movement. Before SNCC, most civil rights leaders were adults, with only a few exceptions like the Southern Negro Youth Congress (SNYC) in the 1930s and ’40s. While the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) had some young leaders in the 1960s, SNCC had more people working full-time in southern communities than any other civil rights organization. On February 16, 1960, Martin Luther King Jr. spoke about the importance of young people in the fight for civil rights at the White Rock Baptist Church in Durham, North Carolina, saying, “What is new in your fight is the fact that it was initiated, fed, and sustained by students.”

The Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) played a significant role in the civil rights movement by organizing from the bottom up and bringing new voices to the movement. SNCC was founded just two and a half months after the Greensboro sit-ins in 1960, and Ella Baker was instrumental in organizing the new student activism. SNCC primarily engaged in protests aimed at desegregating lunch counters and restaurants. Still, Baker maintained a conversation about grassroots organizing and sent Robert “Bob” Moses, on a journey through the Deep South to recruit students to participate in an SNCC conference planned for October 1960.

SNCC’s priority was direct action. Discussions on how to spread the sit-in movement dominated. President John Kennedy and his brother, Attorney General Robert Kennedy, were hostile to direct action and began pressing SNCC to turn to voter registration. SNCC was hesitant to abandon protests and turn to voter registration, as they saw it as selling out and wondered what it would mean for radical, systemic change. Ella Baker helped the young SNCC organizers reach a consensus to establish a direct action and voter registration wing. SNCC slowly evolved into an organization of organizers, embedding themselves in rural communities where they gave special emphasis to voter registration. SNCC’s first voter registration effort began in McComb, Mississippi in the late summer of 1961, which was the most Klan-ridden region in the state. Despite encountering violence at a level it never had before, new leaders emerged, and some 80,000 Black people registered. In April 1964, SNCC workers organized the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party (MFDP) and decided to challenge the legitimacy of the all-white “regular” state party. What has become known as the 1964 Freedom Summer was violent and bloody. During the search for the bodies of three SNCC workers, the unidentified bodies of five Black men were pulled from Mississippi rivers. Scores of the volunteers and SNCC organizers were arrested and beaten. In August, an MFDP delegation went to the Democratic Party National Convention in Atlantic City, New Jersey, to challenge the legitimacy and seating of the all-white Mississippi delegation there. Although there was sympathy for the plight of Black Mississippians, they were not seated.