Voices of Change: Washington, Du Bois, and the Fight for Black American Progress

Explore the ideological debates between Booker T. Washington and W.E.B. Du Bois then lead students in a debate of their own.

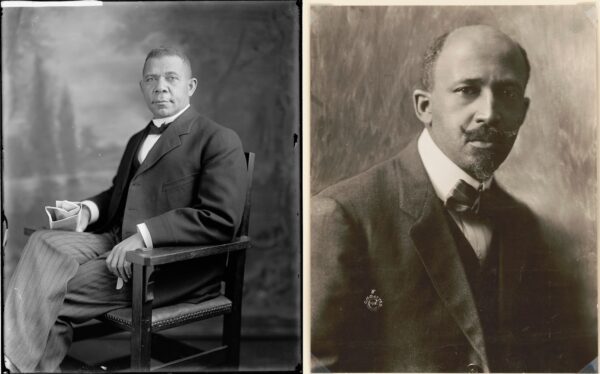

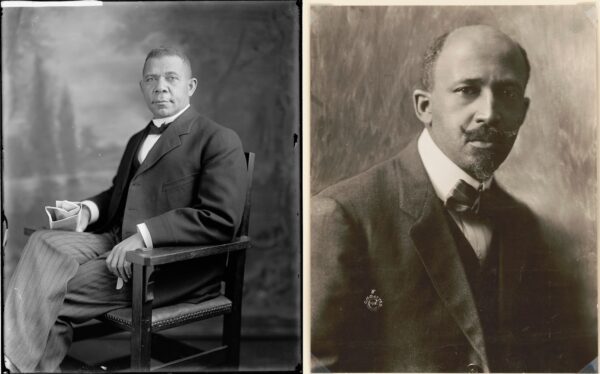

In the late 1800s and early 1900s, several significant periods and events happened in or impacted the United States (e.g. post-Reconstruction, World War II, the Great Depression). In this context, as Black Americans desired and, in many instances, demanded social and economic progress and civil rights, two leaders – Booker Taliaferro Washington and William Edward Burghardt (W. E. B.) Du Bois – rose to prominence for their views regarding the best ways to achieve progress. While both men were adamant about enhancing the lives of Black Americans, their ideologies were different. Washington promoted industrial education, hard work, and financial prosperity as the best strategies for Black Americans to earn respect from and develop racial solidarity with white Americans. Conversely, Du Bois promoted academic education, a civil rights agenda, and political action as the best strategies for Black Americans to secure progress. While Washington died in 1915 and Du Bois died in 1963, both leaders’ ideologies greatly influenced and shaped Black American progress and the Civil Rights Movement of the 1950s and 1960s. Their differing ideologies continue to be debated and referenced as historically significant and relevant today.

Not only did Washington and Du Bois have different Black American progress ideologies, but they also had different experiences in terms of their upbringing, education, and experiences. Washington was 12 years Du Bois’ senior, the child of an enslaved family on the Burroughs plantation in Hale’s Ford, Virginia. He attended school for the first time in 1865 after the Civil War ended. He attended Wayland Seminary and Hampton Normal and Agricultural Institute (now Hampton University) before returning to Malden, West Virginia to teach. Washington taught at Hampton before accepting the position to open and lead Tuskegee Normal School for Colored Teachers (now Tuskegee University). Du Bois was born in 1968 to a free Black family in Great Barrington, Massachusetts. He experienced racism but grew up in a predominantly white community where he attended integrated schools. After graduating from Searles High School, he attended Fisk University in Nashville, Tennessee, followed by Harvard University in Boston, Massachusetts. Du Bois was the first Black person to earn a Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) from Harvard University.

Undoubtedly, their upbringing, education, and experiences played roles in their ideologies. Washington experienced the limitations of enslavement and believed his hard work and industrial education prepared him well to lead other Black Americans in a similar pursuit of progress. Du Bois experienced the freedom of living in a multiracial community, attending an integrated school, with teachers who encouraged his intellectual pursuits. As a result, Du Bois believed academic education and an aggressive demand for civil rights were the foundations of Black American progress.

The differences in these scholars’ perspectives set the stage for a conflict that is still discussed today. Although Du Bois initially wrote favorably to Washington after his “Atlanta Address,” stating that Washington ‘s speech was “fitly spoken,” he later criticized the speech and Washington’s Black progress ideology as one that appeased white people and centered on segregation and submission. The conflict between the two men reached its pinnacle when Washington was said to try to neutralize his most vocal critic, by recommending Du Bois to the position of Superintendent of Negro Schools of the District of Columbia. In a private letter, Washington informed Du Bois that he had recommended Du Bois as fiercely as he could. Du Bois later stated that he did not apply for any such position. In 1901, Du Bois was offered the opportunity to edit a national magazine headquartered at Hampton. He declined the offer when he was told that the final decisions regarding the editorial would come from Tuskegee, and he was ambivalent about oversight by Washington. In 1902, Du Bois received several offers of employment at Tuskegee for a significant salary increase. Du Bois considered the offer and was interviewed by Washington several times, but ultimately declined, reportedly, because Washington was not clear on the exact nature of Du Bois’ pending appointment.

Evidence of the Washington-Du Bois conflict was represented in the attempts to neutralize all who opposed Washington. White politicians considered Washington to be the leader and speaker of the Black community. Consequently, Washington has their financial support and backing. and the support of white southerners who sought to delay desegregation and civil rights as long as possible. Du Bois perceived Washington’s influence as an overreach, noting that Washington created the “Tuskegee Machine” of supporters, philanthropists, educators, business people, and politicians who not only supported Washington and created Tuskegee-modeled educational spaces, but also limited Washington critiques via the control of Black media.

The Washington-Du Bois conflict was apparent in Washington’s and Du Bois’ competing essays in The Negro Problem (1903). Washington’s essay, “Industrial Education for the Negro” and Du Bois’ essay “The Talented Tenth” outlined their Black progress ideologies and subsequent critiques of the other’s ideology. Du Bois presented a scathing critique of Washington in the essay “Of Mr. Booker T. Washington and Others” in The Souls of Black Folks (1903). Washington attempted to address the conflict by inviting Du Bois and other scholars to discuss their concerns via the Washington-Du Bois Conference held January 6-8, 1904, in New York at Carnegie Hall. Very little was known about the conference; however, a few months prior, Du Bois anticipated that his attendance at the meeting would be aligned with “Principles of Anti-Washington men, “in opposition to any organization not focused on full civil rights for Black Americans; criticism of Washington’s beliefs regarding civil rights, education. was the result of the meeting resulted in a Committee of Three and later a Committee of Twelve, meeting periodically to discuss and vote on Black American progress issues. The committees most often aligned with Washington.

Featured in

Explore the ideological debates between Booker T. Washington and W.E.B. Du Bois then lead students in a debate of their own.