The Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party’s challenge to be seated at the 1964 Democratic National Convention was defeated because of President Johnson’s work behind the scenes to undermine their efforts. In light of this, opinions on whether to continue to support Johnson’s bid for reelection were mixed following the convention. Though there were SNCC activists who campaigned for Johnson, the organization did not offer their official support. Many felt disillusioned after Johnson’s betrayal, and they doubted the value of being under the national Democratic umbrella.

Some in SNCC discussed the need for an independent Black political party in Mississippi but were unwilling to fight the MFDP, which was still led by local community leaders. “You can’t say that people have a right to make the decisions affecting their lives and then turn around and fight them because they made a decision you disagree with. The MFDP belongs to the Mississippians, not SNCC,” said one SNCC organizer. The leaders of the MFDP were not naïve, they understood Johnson was behind their defeat. However, they also recognized that even in defeat their association with the national Democratic party and their efforts in Atlantic City had generated a great deal of traction for their efforts within the state.

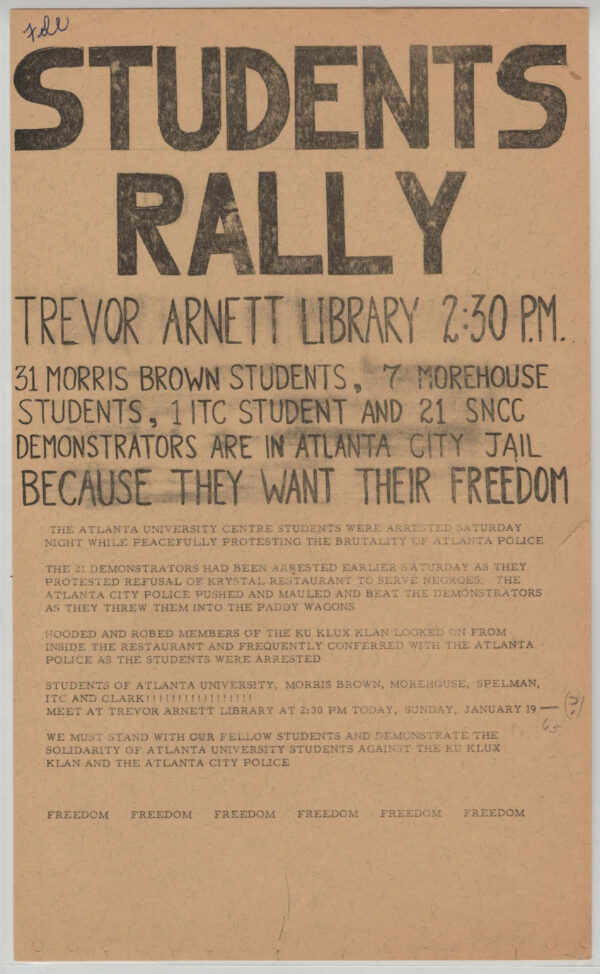

In March 1965, a group from SNCC (Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee) used the Selma-to-Montgomery March to connect with interested Black residents and start organizing in Lowndes County, Alabama. SNCC had been organizing in Selma since February 1963 but had not yet extended its efforts to Lowndes County. Even though Lowndes County had an eighty percent Black population, racial terrorism kept Black people from even attempting to register to vote. In fact, the only people anyone knew who had even attempted to register had done so only a few weeks before SNCC had arrived, and they were still waiting for confirmation.

Led by Stokely Carmichael, this SNCC group was eager to dig in on the issues that were of the greatest local interest. Initially, the main issues were much the same as they had been: offering education, advocating for desegregation and school improvement, and increasing voter registration. However, after the passage of the Voting Rights Act in 1965, SNCC begins to ask locals a new question, “What are you going to do with your vote?” and the answer was “Form our own party.” Eager to pursue new strategies following the betrayal at the DNC, Carmichael and SNCC were ready to help.

John Hulett, who had already formed the Lowndes County Christian Movement for Human Rights with a small group of other Black residents, was an obvious choice of leader for the potential new party. Together they formed the Lowndes County Freedom Organization (LCFO), with Mr. Hulett serving as its chairperson. The party adopted the symbol of a pouncing black panther. Within a year, most voters in Lowndes County were Black. Once the LCFO had enough registered voters, they were able to officially become the Lowndes County Freedom Party (LCFP). By 1968, the LCFP merged with the national Democratic party. In 1970, John Hulett, who had been part of the group trying to register to vote prior to SNCC’s arrival, was elected as the county sheriff.

By 1966, SNCC elected Stokely Carmichael to replace John Lewis as chair, a clear sign that the organization had shifted away from emphasizing moral solutions to the problem of white supremacy and more toward political solutions. While John Lewis remained more aligned with the strategies of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference and Dr. King, Stokely Carmichael was an increasingly vocal Black Power advocate. The shift to seeking political solutions to the civil and human rights crisis faced by Black Americans was at the heart of the Black Power movement and the many organizations that began to emerge.

The same year that Carmichael became chair at SNCC, Bobby Seale and Huey Newton established the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense (BPPSD) in Oakland, California. Like Malcolm X, the Black Panthers believed that nonviolent protests were not enough to free Black Americans or give them control over their own lives. The Panthers’ founding document was the “Ten Point Platform,” which was widely distributed as a means of propaganda, education, and recruitment. The party also initiated various pioneering community programs, mostly led by women, in the Oakland area. The most famous and successful of these programs was the Free Breakfast for Children Program, which began in a San Francisco church and fed thousands of children throughout the party’s history. Today, public schools’ free breakfast programs are a legacy of the Black Panther Party.

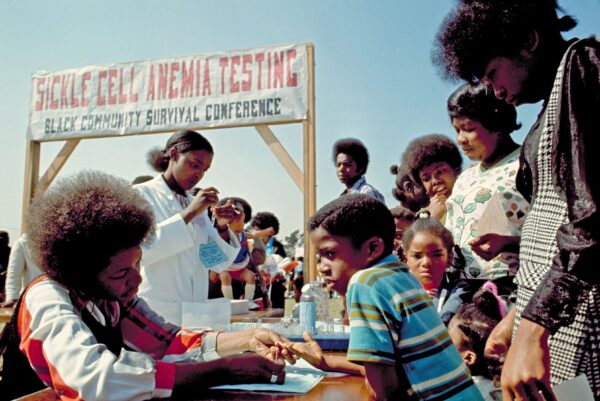

Other free services offered by the Black Panthers included clothing, classes on politics and economics, medical clinics, lessons on self-defense and first aid, transportation for family members of inmates to upstate prisons, an emergency response ambulance program, drug and alcohol abuse rehabilitation, and testing for sickle-cell anemia. The Panthers tested over 500,000 community members for this disease before it was officially recognized as mainly affecting the Black community. The Party also worked to end drug use in the Black community by disrupting drug dealers, distributing anti-drug propaganda, and setting up community drug rehabilitation programs.

In 1967, the Black Panther Party organized a march to the state capital in Sacramento to protest the state’s attempt to prohibit carrying loaded weapons in public. Major news coverage of the protest, including images of Black participants carrying rifles in front of the capital, put a spotlight on the organization. The Panthers continued to gain popularity among Black communities in California and soon began expanding beyond the state.

While some members of the organization focused on community programs and services, others became involved in confrontations with the police. Their successes in both organizing community support programs and their defiance against the police made them a prime target. Police and government officials subjected the group to endless prosecutions, shootouts, investigations, surveillance, and even assassinations. Overtime, however, the separation between planning political actions, clashing with the police, providing community services, seeking access to power, and cultivating a grassroots identity became confusing and contradictory. Eventually, the Black Panther Party fell apart due to political, legal, financial, and interpersonal issues. Many members, however, continued to be involved with both the practical and ideological work of Black liberation.